Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE)

Approximately 900,000 people in the United States are affected by DVT every year. This problem is even more common in hospitalized individuals and in these with chronic medical conditions or trauma. Half of all DVT patients will have long term complications such as post-thrombotic syndrome, swelling, pain, discoloration, and scaling of the affected limb. Estimated 60,000-100,000 patients lose their lives as a result of VTE.

Pathophysiology

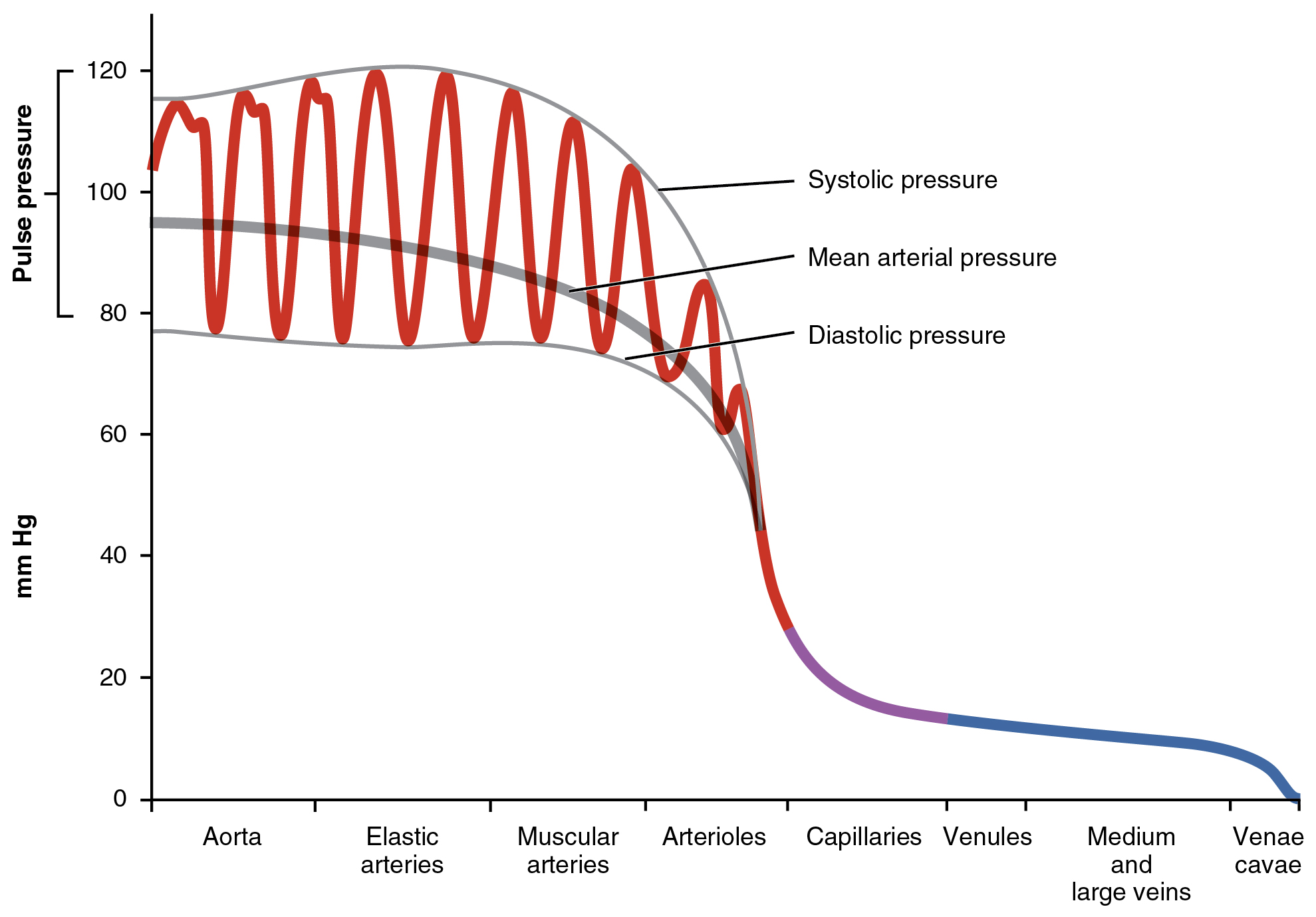

Veins in the human body return the deoxygenated blood into the heart and to the lungs to be replenished. A blood clot can develop anywhere along this path. Blood flow is proportional to the pressure difference between the venous system and the right atrium and inversely proportional to the resistance in the same vessel. Therefore, anything causing resistance in the blood vessels will slow the flow of blood. On average the arterial blood pressure is around 100mmHg while the venous pressure is 5-10mmHg. Blood in the veins needs additional assistance to get back up to the heart.

Picture 1. Arterial pressure compared to venous pressure.

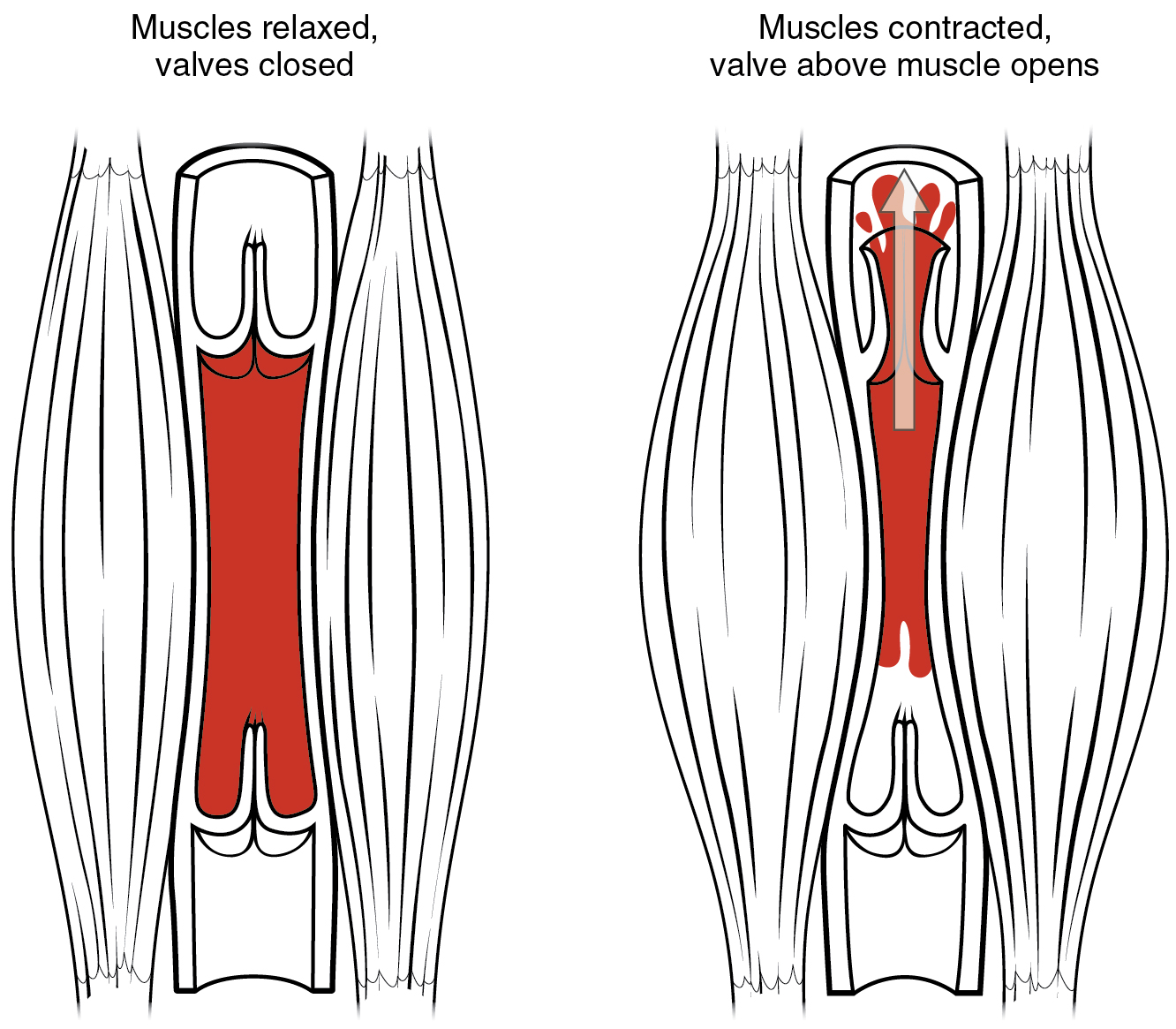

In both lower and upper extremities, the venous system is made up of superficial and deep veins, with respect to the muscular fascia. The superficial veins join with the deep veins at the groin and the axilla. In order to return the deoxygenated blood towards the heart, the veins of the extremities have a series of one-way valves that prevent retrograde blood flow and direct the blood into the deep veins and the large veins of the trunk. Additionally, muscles (particularly in the calf) also assist with compression of the veins, functioning as a peripheral pump for the returning of blood. Swelling of the feet can occur if someone has been standing or sitting for too long.

Picture 2. When muscles contract the valves open and allow the blood to move up towards the heart. When they relax the valves are closed shut.

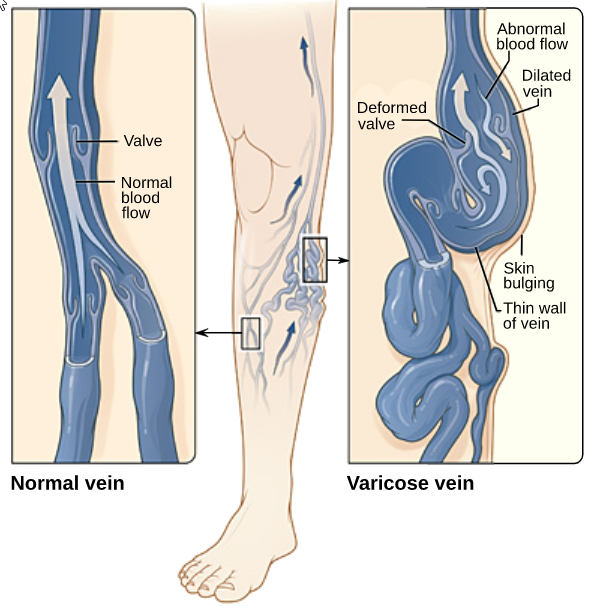

If the valves lose their functionality, blood stagnation and hypertension occur in the gravity-dependent parts of the body (lower extremities commonly). Over time valves may become leaky, resulting in venous insufficiency. Venous thrombosis involves veins of the lower extremities in 90% of the cases, while the remaining 10% involve the thoracic and upper extremity veins.

Picture 3. Incompetent valves result in venous insufficiency

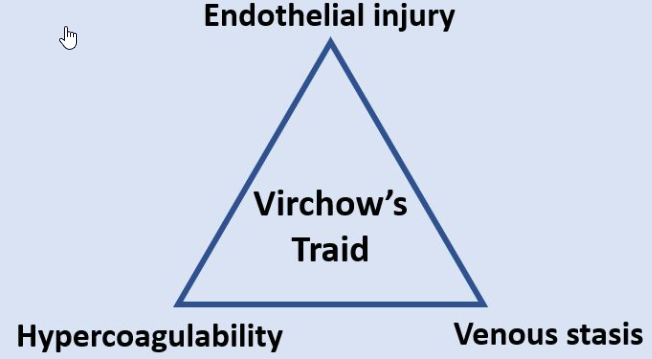

A number of conditions increase the risk of thrombosis formation and result in deep vein thrombosis. These are known as Virchow's triad:

Picture 4. Virchow's triad makes up the various factors that result in thrombus formation

| Virchow's triad | Venous stasis | Hypercoagulability | Endothelial injury |

| Risk factor | Immobility | Factor V Leiden syndrome | Trauma |

| Risk factor | Hospitalization | Anti-thrombin III | Surgery |

| Risk factor | Obesity | Antiphospholipid syndrome | Infection |

| Risk factor | Surgery | Protein C or S deficiency | Indwelling catheter |

| Risk factor | Pregnancy | Oral contraceptives (birth control) | |

| Risk factor | Previous DVT | Prothrombin 20210 | |

| Risk factor | Heart disease | ||

| Risk factor | Age |

Thrombosis that forms in the superficial veins is known as superficial venous thrombophlebitis. Although it is often painful and swollen, it is not a dangerous condition and often resolves with anti-inflammatory medications and warm compresses. It can be confused with cellulitis, however, there is no infection and antibiotic treatment is not indicated. If thrombophlebitis gets infected, it is known as a suppurative (septic) thrombophlebitis and is treated with antibiotics with or without surgical excision. Sometimes superficial thrombophlebitis may have the potential to mobilize into the deep venous system (Picture 5) and will, therefore, require additional treatment with anticoagulants.

Picture 5. Deep vein thrombosis. Although harmless most of the time superficial venous thrombophlebitis can dislodge into the deep veins and lead to a PE.

Presentation

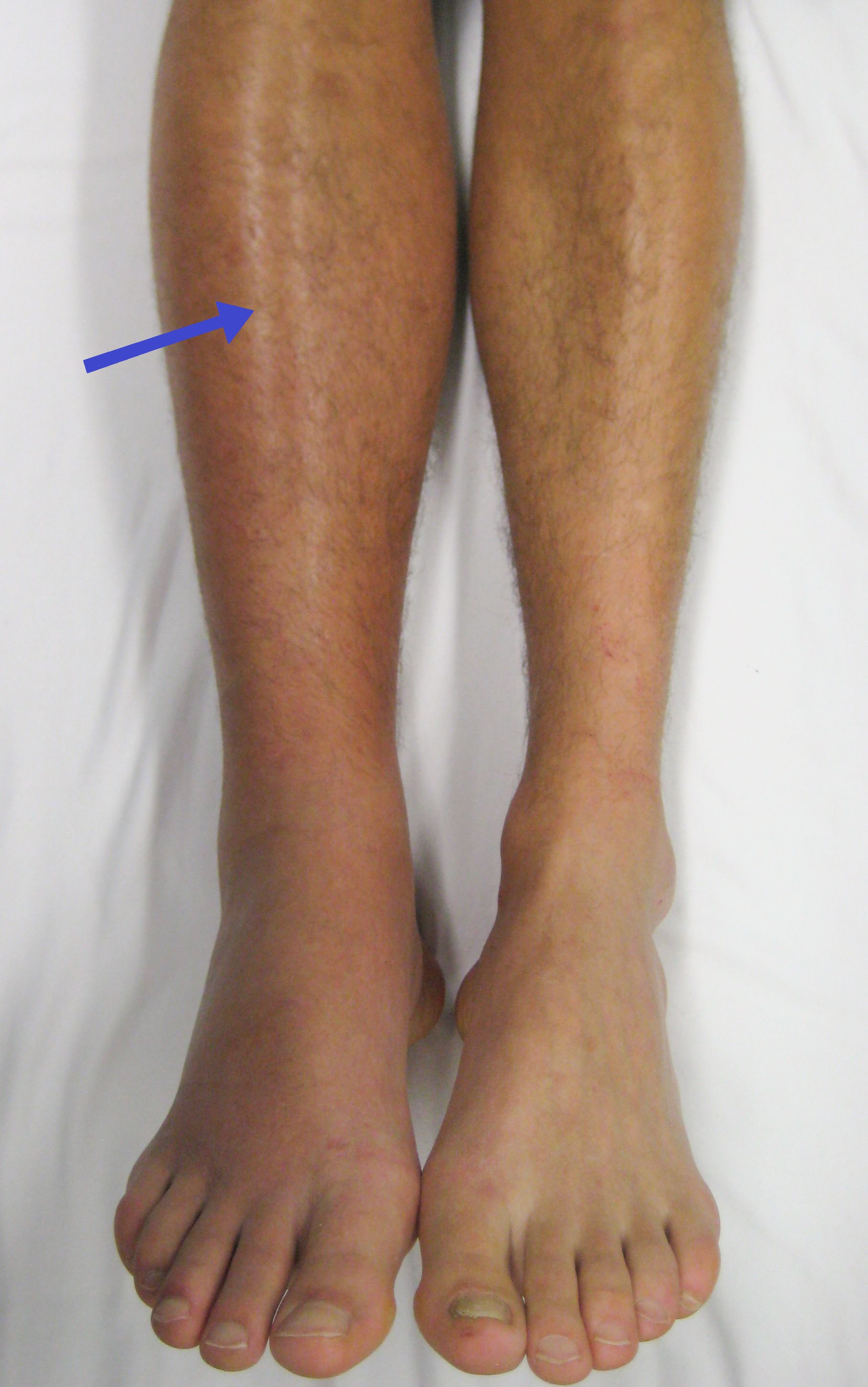

DVT usually presents with extreme swelling but this can be variable depending on the extent of the thrombosis and the collateral pathways. Therefore the possibility of a DVT should always be kept in mind. Occasionally a DVT can progress into serious complications such as phlegmasia cerulea dolens (Picture 6). This condition is characterized by a massive thrombosis of the deep system. The limb becomes dusky, blue or cyanotic due to the nearly complete venous obstruction at the iliac and femoral veins. The swelling becomes very severe and the arterial tissue blood flow is impaired at the capillary level. There is a significant risk of compartment syndrome, gangrene, and other serious complications. Phlegmasia alba dolens represents a milder form of venous thromboembolism that results in arterial compromise. At this stage, the limbs are pale and white but not cyanotic yet. Both of these disorders must be treated quickly.

Picture 6. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Nearly complete venous obstruction at the iliac and femoral veins.

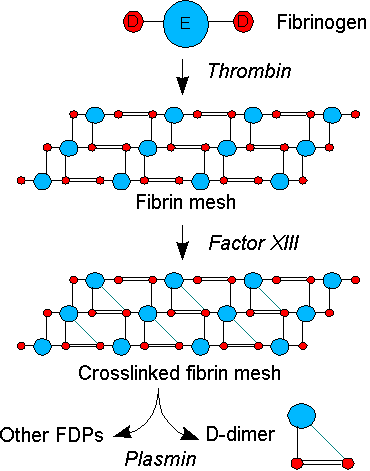

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the most significant complication of DVTs that can be fatal. In this case, a portion of the thrombus breaks free and travels in the blood vessels towards the pulmonary arteries where it can block the blood flow. Severe PEs can be classified as massive and submassive.

Picture 7. CT imaging of a saddle embolism which is a type of a pulmonary embolism that can be fatal.

Long term complications of DVTs caused by damaged venous valves can result in chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) which can have a range of symptoms referred to as post-thrombotic syndrome.

Picture 7. Chronic venous ulcers tend to be between the lower calf and the medial malleolus

History of a suspected DVT

The most important factors to analyze are duration of symptoms, family history of thromboembolism, and other risk factors such as prior DVT or PE, medications, malignancy, surgery, or recent travel.

- Upper or lower limb pain

- OPQRST

- Is the pain unilateral?

- Swelling?

- Is the swelling unilateral?

- How much can you walk?

- Do you have any pain while walking?

- No pain while walking reduces the chances for the presence of an arterial-occlusive disease or arthritis

- Any history of recent travel?

- Long car rides or air travel?

- Do you have new chest pain or breathing difficulty?

- Age?

- Obesity?

- Big 6

- PSHx

- What surgery?

- When?

- How was recovery from the surgery?

- Was the recovery sedentary?

- PMHx

- History malignancies

- There is an increased risk of DVTs with all types of cancers that falls overtime with treatment

- History malignancies

- Medications

- Social

- Smoking

- FAMx

- Family history of vascular disease such as varicose veins

- PSHx

Physical exam

The exam should be comprehensive for vascular, orthopedic, and nonvascular (e.g. cellulitis) issues. If a DVT is suspected, a PE must be ruled out by assessing the patient for hypoxia, tachycardia, and signs of right heart strain (e.g. jugular venous distention). If a VTE is suspected, we must first ensure that the patient is hemodynamically stable before beginning the peripheral vascular exam.

The vascular exam focuses on the arterial, venous, and lymphatic systems. It is the same for the upper and lower extremities. The exam includes inspecting extremities, palpating for pulses, tenderness, and palpating lymph nodes.

- Inspection

- Leathery changes - indurations due to venous stasis and venous hypertension

- Hyperpigmentation - lipodermatosclerosis

- Ulcers

- Asymmetry

- Limb girth

- Tenderness of the calf

- Shiny skin

- Presence or absence of hair (consistent with arterial insufficiency)

- Palpation

- Femoral pulse and lymph nodes

- Popliteal pulse

- Posterior tibial and Dorsalis pedis pulses of the feet

- Capillary refill time <2 seconds is considered normal

- Neuro exam

- Sensation

- Touching the toes and under the feet

- Motor

- Wiggling toes

- Sensation

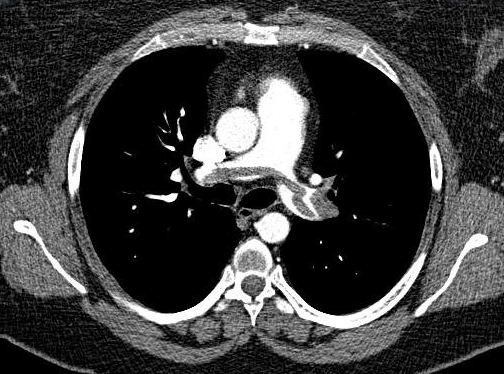

Prior to obtaining any other diagnostic testing Wells' or Caprini risk assessment models for DVT can be used.

Picture 8. Wells' criteria for a PE taken from mdcalc

Investigations

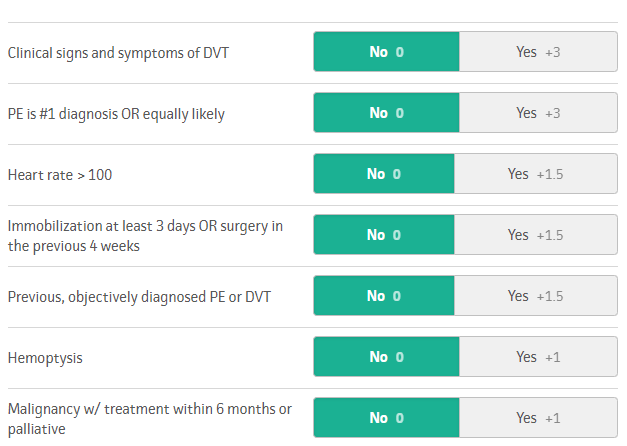

There are several tests for patients who are suspected to have a DVT. The only blood test used commonly is known as the D-dimer test. D-dimer is one of the final products of the coagulation pathway and the amount of this substance increases when coagulation takes place. This test is very sensitive but not very specific as there are a number of conditions in the body other than a DVT that can elevate the levels of this product in the blood. This means that a negative D-dimer test essentially rules out the presence of a DVT but a positive one cannot confirm the same diagnosis. Trending D-dimer levels can be used to monitor the progress of therapy. Additionally, D-dimer levels can be falsely elevated in patients who are obese, pregnant, and elderly.

Picture 9. Coagulation pathway with D-dimer and fibrin degradation product formation.

In a suspected case of a PE there are several tests to assess the patient:

- Arterial blood gas (ABGs) - shows a disparity in ventilation and perfusion

- Hypoxia

- Widened A-a gradient

- Respiratory alkalosis

- Hypocapnia

- Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) and troponin

- Determine how severe the PE is and help diagnose a submassive PE

- ECG and echocardiogram

- Tachycardia

- RV strain

- Non-specific T-wave changes

- Non-specific ST-segment changes

- S1Q3T3

- New incomplete RBBB

- Right heart strain

In patients with recurrent or unprovoked DVTs, it is important to assess for underlying conditions such as undiagnosed malignancies or hypercoagulable state. Blood tests may help determine if the patient has underlying conditions such as factor V Leiden thrombophilia and prothrombin 20210 gene mutation. These patients should be referred to a hematologist after the thromboembolic condition has been resolved.

Imaging

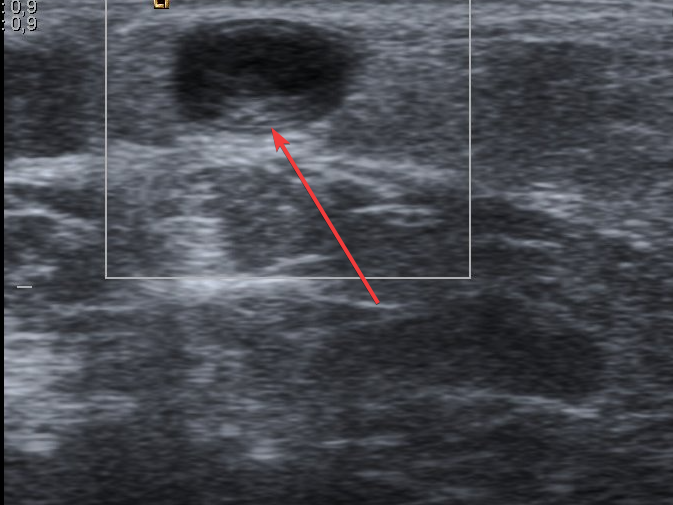

Imaging can play an important role by confirming the diagnosis of a DVT or PE. For a DVT in a hemodynamically stable patient, venous duplex ultrasound is the definitive study to confirm the diagnosis of a DTV. The veins are observed and compressed. If a thrombus is seen or a vein is not compressible the diagnosis of a DVT is made.

Picture 10. Thrombus in the great saphenous vein seen on Ultrasound.

This test is non-invasive and has no radiation side effects. Duplex U/S can classify the DVT as acute or chronic. Chronic DVT does not require anti-coagulation and is a sign of a now-healed acute DVT. If a thrombus is seen propagating up into the iliac veins ordering an MRI or CT scan with venous contrast (known as MRV and CTV) should be considered in order to assess the proximal extent of the DVT.

In the diagnosis of a PE, CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) is the most sensitive and specific imaging modality and is the first choice for initial evaluation (Picture 7). It involves the use of contrast and the risks of radiation. Additionally, ECG and echocardiogram can be used to assess for right heart strain in patients with severe PE. Tachycardia and non-specific ST changes are the most commonly seen signs of a PE on ECG. An echocardiogram can help visualize the pulmonary artery and the 4 chambers of the heart dynamically (Picture 11).

Picture 11. Echocardiogram visualization of the heart and the 4 chambers.

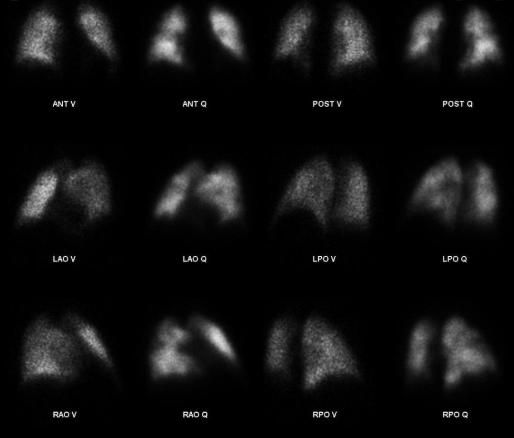

Another modality for patients of suspected PE is a Ventilation/Perfusion (V/Q) scan. This test is ideal for patients who cannot undergo CTPA due to contrast allergy, renal insufficiency, or morbid obesity. In the ventilation component, the patient inhales a radiolabeled aerosol. This is followed by a perfusion scan where the pulmonary blood is labeled by a radioisotope. A mismatch between the two suggests the presence of a pulmonary embolus.

Picture 12. V/Q scan can be used to detect a PE in patients who cannot get a CTPA

Decision making

Initial treatment for an uncomplicated DVT is outpatient anticoagulation for 3-6 months if the patient doesn't have any contraindications. Patients suffering from uncomplicated asymptomatic below the knee DVT are not given anticoagulation as they can be managed expectantly with surveillance serial ultrasound. If their DVT progresses on imaging they can be treated with anticoagulation. In the past, most patients with DVT were started on heparin and then switched to warfarin. Nowadays patients are managed with newer direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Some patients are prescribed warfarin with the Lovenox bridge. As a result, a majority of patients with DVT can be treated as outpatients. DOACs work by directly inhibiting thrombin. Some examples of traditional anticoagulation medications and DOACs are shown below (Table 1).

| Drug | Brand name | Route | Reversal | Half-life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heparin | Heparin | IV, Sub Q | Protamine | 1-2 hours |

| Warfarin sodium | Coumadin | Oral | FFP, PCCs, vitamin K | 20-60 hours |

| Enoxaparin | Lovenox | Sub Q | Protamine (partial reversal) | 5-7 hours |

| Rivaroxaban | Xarelto | Oral | Andexanet alfa (Andexxa) | 5-9 hours, 9-13 hours in elderly |

| Dabigatran | Pradaxa | Oral | Idarucizumab (Praxbind) | 12-17 hours |

| Fondaparinux | Arixtra | Sub Q | 17-21 hours | |

| Edoxaban | Savaysa | Oral | 10-14 hours | |

| Apixaban | Eliquis | Oral | Andexanet alfa (Andexxa) | 9-14 hours |

DOACs do not require frequent blood tests and are safe in outpatient settings. The inability to reverse these agents has been a concern in the past but reversal agents are becoming more and more available. Note that these reversal agents are changing often and it is important to refer to guidelines such as the chest guidelines. There are several absolute and relative contraindications for anticoagulation (Table 2).

| Absolute | Relative |

|---|---|

| Active bleeding | Recurrent bleeding from multiple GI telangiectasias |

| Severe bleeding diathesis | Intracranial or spinal tumors |

| Platelets < 50,000 | Platelets < 150,000 |

| Recent, planned, or emergent high bleeding risk surgery or procedure | Large AAA with concurrent severe hypertension |

| Major trauma | Stable aortic dissection |

| History of recent intracranial hemorrhage | Recent, planner, or emergent low bleeding risk surgery or procedure |

Surgery

There aren't many indications for surgery in DVT. 2 of the non-medical surgical options are shown below:

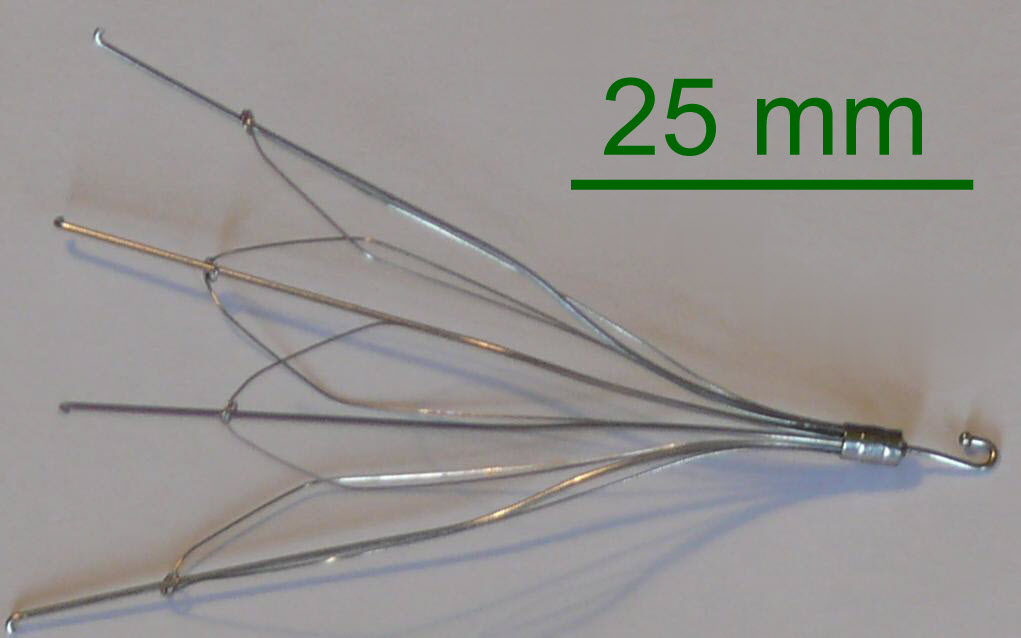

- Temporary IVC filter

- These filters don't address the existing clot

- They decrease the risk of an embolus reaching the lungs and causing a PE. They are placed by a femoral or jugular vein into the inferior vena cava

- They catch the clot and are retrievable

- These filters should be removed within 6-12 months as there is a risk of filter thrombosis

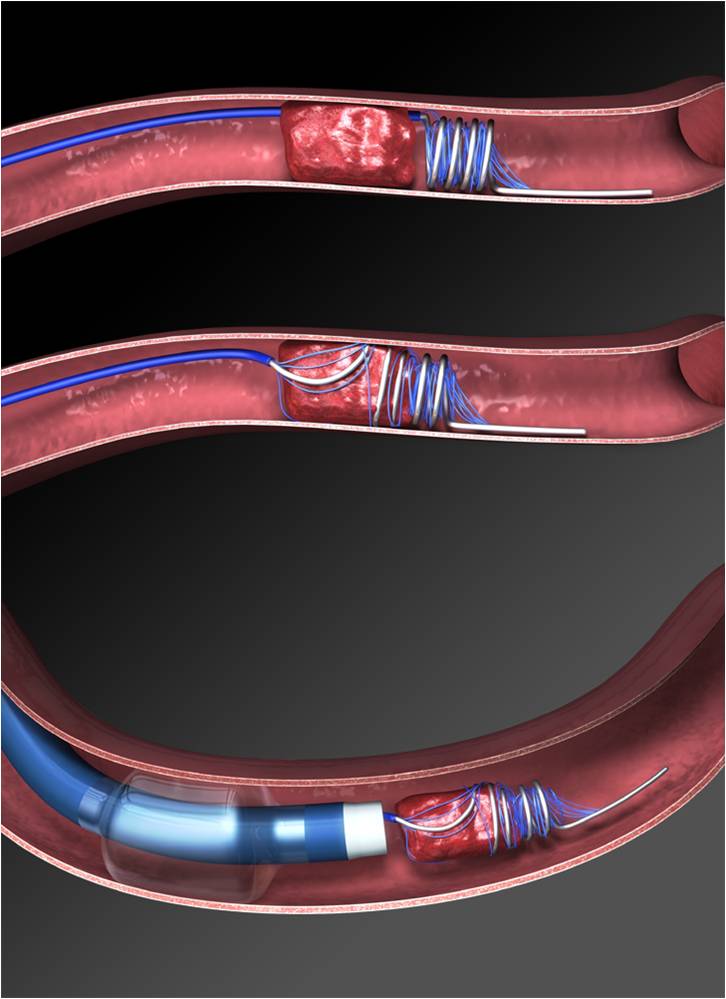

- Thrombectomy

- Another alternative for patients who cannot be on anticoagulant medication is thrombectomy

- Mechanical

- The clot is removed by mechanical means

- The suction device is moved back and forth through the IVC under Xray guidance

- Medication-induced

- Breaks up the clot

- Tissue plasminogen activator (Tpa) dissolves the clot

- Can be given through a peripheral intravenous line (systemic) or directly into the clot through a catheter (local)

- Carries risk of intracranial bleeding

- Should have an IVC filter placed

- Mechanical

Treatment for massive PEs must be done emergently. These patients are hemodynamically unstable and have high mortality. Unless there are contraindications for surgery or cardiopulmonary bypass they should be taken to the OR for surgical embolectomy. Before the surgery IV heparin should be initiated unless there are contraindications.

Patients with a submassive PEs have stable vitals. However, these PEs can turn into massive PEs, and therefore these patients should be monitored carefully. Patients with submassive PE will have evidence of right heart strain often diagnosed through ECG, echocardiogram, and blood tests such as BNP and troponin. IV heparin should be started and if indicated catheter-directed thrombolysis should be initiated within 12-24 hours. There is some controversy in this area as some institutions use systemic thrombolysis instead of local thrombolysis. Either way, these patients receive an IVC filter to prevent another PE.

Patients without the symptoms of PE and without right heart strain or those with an incidental diagnosis of PE can be treated with anticoagulation or be considered for an IVC filter placement if there is a contraindication to anticoagulation while a potential for thrombus propagation and PE. Treatment decisions should be individualized to each patient. The goals of acute treatment are to prevent further extension of the thrombus, prevent recurrence or occurrence of PE, and to relieve the acute symptoms.

Postoperative care

There are multiple long term considerations in patients with a DVT or PE. These are:

- How long to continue anticoagulation?

- DVT

- Most patients with a DVT are recommended to be on anticoagulation for 3-6 months

- Patients with recurrent DVTs or hematological abnormality may require lifetime anticoagulation

- Upper extremity DVT associated with central venous catheter

- Use of the catheter may be continued if required clinically

- Anticoagulation remains while the catheter is in place and 3 months after the catheter is removed

- Longer anticoagulation factors

- Positive D-dimer

- DVT close to the proximal or central veins

- Presence of active malignancy

- History of previous blood clots

- PE

- Anticoagulation at least for 6 months

- Imaging of lower extremities and chest

- Monitor for signs of pulmonary hypertension

- DVT

- Referral to hematology?

- Unprovoked DVT or PE

- These patients may require longer-term anticoagulation especially in the case of a recurrence

- Long term complications?

- Reduce the risks of recurrent thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS)

- PTS includes chronic symptoms such as

- Swelling

- Discomfort

- Discoloration

- Varicose veins

- Venous ulcers

- PTS includes chronic symptoms such as

- Reduce the risks of recurrent thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS)

PTS is a result of venous stasis and insufficiency due to the damage of the venous valves. Although controversial, some professionals have recommended early aggressive thrombolysis to minimize the venous valvular damage to minimize the severity of the post-thrombotic syndrome. CEAP is a comprehensive classification system for venous insufficiency. Read more about CEAP here.

- Clinical signs

- Etiology

- Anatomy

- Pathophysiology

| CEAP classification of chronic venous disease | Clinical classification |

|---|---|

| C0 | No visible or palpable signs of venous disease |

| C1 | Telangiectasies or reticular veins |

| C2 | Varicose veins |

| C3 | Edema |

| C4a | Pigmentation or eczema |

| C4b | Lipodermatosclerosis or athrophie blanche |

| C5 | Healed venous ulcer |

| C6 | Active venous ulcer |

| Etiological classification | Anatomical classification | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| Ec: congenital | As: superficial veins | Pr: reflux |

| Ep: primary | Ap: perforating veins | Po: obstruction |

| Es: secondary | Ad: deep veins | Pr,o: reflux and obstruction |

| En: no venous cause identified | An: no venous location identified | Pn: no venous pathophysiology identifiable |

Ancillary measures such as ambulation, exercise, and compression stockings can reduce the effects of post-thrombotic syndrome.

Patients should be aware of the symptoms of recurrence as well as preventative measures. Proper workup with duplex imaging, lab investigations should be completed. Prompt diagnosis and anticoagulation treatment can prevent PE formation, which can be fatal. The post-thrombotic syndrome should be recognized and managed appropriately.

All information provided on this website is for educational purposes and does not constitute any medical advice. Please speak to you doctor before changing your diet, activity or medications.